by Lynda Denyer

Steyning underpins the story of King Harold’s clash with Duke William

of Normandy in 1066. It has even been said that Steyning was one of the

reasons why King Harold lost his crown!

1. Grant by Duke William to the Church of the Holy Trinity at Fécamp.

Of the land of Steyning [co. Sussex]; the Duke gave seisin to the Church by the token of a knife, before he went to England; the grant to take effect if God should give him victory in England.

Witnesses: Aymeri the vicomte; Richard fitz Gilbert; Pons.

From: Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum 1066-1154 Volume I, edited by H W C Davis (Oxford, 1913).

This is a note of the very first Anglo-Norman charter by William the Conqueror in 1066. It is an oath sworn upon a knife, which sends a shiver down the spine. William’s grant is conditional upon his conquest of England, which is even more curious. The Norman fleet had not yet crossed the sea! On the eve of the most famous event in English history, Steyning was the subject of an extraordinary bargain offered by Duke William, “if God should give him victory”.

Why Steyning? Today it is a picturesque little town nestled beneath the South Downs in West Sussex, with an ancient church dedicated to Saint Andrew.

This dedication apparently dates from its foundation, although an additional dedication was recently made to Saint Cuthman. The church still celebrates its foundation by the Anglo-Saxon Saint Cuthman. The ancient port of Steyning was known as Cuthman’s port. Pilgrims once flocked to the church to visit his shrine and King Aethelwulf was buried there in the year 858. Aethelwulf was the father of King Alfred, who bequeathed Steyning to his nephew in his will. Strange to say, Steyning was also a powerful justification for Duke William’s attack against King Harold.

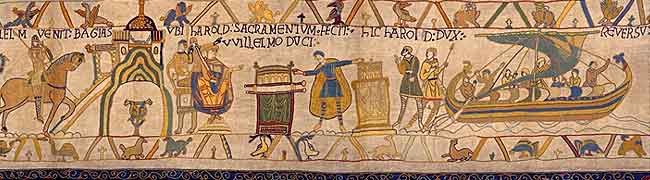

The Bayeaux Tapestry tells the conquest story as the Normans wanted it to be remembered. This is still the version most familiar to us today. King Edward the Confessor promised Duke William the crown of England and Earl Harold swore upon two caskets of holy relics to support the Norman succession. When Edward died, Harold broke his solemn promise and took the crown for himself.

William made a great deal of Harold’s oath after the Conquest, but the story was not a very persuasive call to arms when William first proposed his dangerous adventure. Harold was an impressive leader who had been annointed before God and crowned in peace by the will of his people. There were further Norman accusations about malpractice in the English Church but these only brought to mind the similar or worse condition of other European churches, including Normandy itself.

Duke William had another charge against his rival. It was that Harold withheld for himself what Edward the Confessor had given to the Abbey of Fécamp in Normandy, namely Steyning and its church. This accusation was broadly true. It was, more importantly, dramatic proof of Harold’s contempt for the Roman Church because of the special status included with King Edward’s gift. Steyning had been taken out of the control of the English bishops and given into the personal charge of the Pope. Depriving the Pope of his dominion was an exceptionally serious offence.

This and other damning propaganda against Harold won William papal support. The Roman Church was ever seeking to tighten its grip on European politics and to enforce the obedience of kings. The Pope gave William a consecrated banner and some holy relics to rally troops for the coming battle. King Harold was excommunicated. Papal approval was the deciding factor which gained William the coalition of support necessary for his high risk venture. Powerful men flocked to his banner, encouraged and excited by the prospect of a Holy War or Crusade.

Edward the Confessor spent about twenty eight years in exile before becoming King of England. While the Dane, King Cnut and his two sons occupied the English throne, Edward found sanctuary with the dukes of Normandy. His parents had fled to the court of his maternal uncle, Duke Richard II, where he remained after the death of his father King Aethelred and the return to England of his Norman mother Emma. Documents from the period show that Edward was in the coastal town of Fécamp, where the dukes maintained a palace and lavished their wealth on a great abbey. Edward’s apparent vow of chastity is one of several indications that he may have become a monk at Fécamp, or at least chosen the simple life as a guest of the abbey for many years.

Edward’s prospects of regaining his father’s throne looked dismal. His mother entered into a remarkable second marriage. She became the wife of King Cnut – and had a son. Aethelred’s Norman marriage had been intended to cement a cross-channel coalition against Viking raiders. It was a spectacular failure: the Danish invader Cnut took the throne and the Queen! Others in Edward’s family were murdered. Nonetheless, Richard II’s son, Duke Robert, recognised his cousin Edward as the rightful king of England. Robert even attempted an attack on Cnut from Fécamp, in Edward’s support, but with little success.

Cnut’s line eventually failed and Edward returned to England. His peaceful accession to the throne in 1042 was a dramatic turn of fortune. Edward had much for which to thank his Norman protectors and gave the royal minster church in Steyning, with its large manor lands, to the Abbey Church of the Holy Trinity at Fécamp. The gift was to take effect after the death of the Bishop of Winchester who had charge of Steyning, named Aelfwine.

This man originally accompanied Queen Emma to England from Normandy on the instruction of her father, and Aelfwine became a favourite with whom she was later accused, scurrilously, of having an affair. During the reign of her son Edward, so the story goes, she is said to have walked barefoot over nine red hot metal ploughshares to demonstrate her innocence. Aelfwine had fought against the Danes and became a monk when Cnut took the throne. Upon Emma’s return to England as Cnut’s queen, she raised Aelfwine again to high office. Bishop Aelfwine died in 1047 and ecclesiatical jurisdiction in Steyning then passed via Fécamp Abbey directly to the Pope. This was because Fécamp Abbey itself answered to no Norman bishop but only to the Pope.

An awkward question was whether Fécamp Abbey also answered to the French King, who was technically the lord of its greatest patrons, the Dukes of Normandy. This was conveniently obscured by the politics of Norman relations with France, but what was the position when the abbey gained land from an English King? King Aethelred in exile, Queen Emma of Norman birth, the Danish King Cnut, his two succeeding sons, and the monkish King Edward all seemed oblivious to this problem.

King Edward’s gift may have been influenced by the reunion with his mother, after many difficult years, and memories of his father. King Cnut had already given a port with land around Rye, Winchelsea and Hastings to Fécamp Abbey, to honour a promise made by King Aethelred. Aethelred had taken refuge in Fécamp and left his family there before he died. Not to be disadvantaged by Aethelred’s loss of life and kingdom, the abbey obliged Queen Emma to persuade her new husband, Cnut to pay the price of her family’s safe-keeping. King Edward added the important new Sussex port of Steyning to enrich the abbey’s trade and communication with England. His extraordinary gift was confirmed in a charter up to forty years later under King William, but the monks described the exceptional liberties they believed Edward had given them in a forged charter:

253. Charter by William I to the abbot and monks of Fécamp.

Confirming the gift, made by Edward the Confessor, of Steyning [co. Sussex]. This charter acquitted the grantees of all earthly service and subjection to barons, princes, and others, and gave them all royal liberties, custom, and justice over all matters arising in their land; and threatened any who should infringe these liberties with an amercement of £100 of gold.1

From: Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum 1066-1154 Volume I, edited by H W C Davis (Oxford, 1913).

King Edward was made a saint in later times but his reign was weakened by over-mighty subjects. One of these men, raised up by King Cnut, was Earl Godwine of Wessex. Godwine’s political instincts were Anglo-Danish rather than Anglo-Norman. He was a shrewd and intelligent statesman, but above all he promoted his own family interests. Edward apparently intended to maintain a vow of chastity, but was obliged to marry Godwine’s daughter Eadgyth.

The Earl held vast estates in Sussex formerly owned by the royal family. He may, in fact, have been a direct male-line decendant of King Aelthelwulf, according to the historian Frank Barlow. Godwine’s father, Wulfnoth Cild of Sussex was deprived of his lands after a notorious act of treason under King Aethelred in 1009. In 1051, Godwine also launched a chaotic rebellion and suffered exile. But he returned stronger than ever, unlike his father, and forced several influential Normans to flee the country in 1052. One of these was the Norman Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert of Jumieges, the man suspected of having first suggested to Duke William that he was Edward’s heir.

The monks of Fécamp lost Steyning, having hardly had time to establish themselves, and Godwine took it for himself. The abbey was arguably compensated for this loss in 1054, when Abbot John of Fécamp visited England. King Edward gave the abbot some lands named in a surviving charter, but historians have found it difficult to identify the locations. It seems that the abbey managed to hold on to Cnut’s gifts at Hastings, Rye and Winchelsea.

Maybe Steyning had been Godwine’s by inheritance until his father’s rebellion, when Queen Emma gave it to her favourite, Aelfwine. The terms of King Alfred’s will had stated that his lands must remain with his father’s male decendants, and be returned to them if they should inadvertently fall into the hands of others. This would have included Steyning, which strayed into the possession of Aelfwine and then the Abbey of Fécamp. Did Godwine brandish King Alfred’s will to his own advantage, when others had forgotten it?

As a patriot and statesman, to his credit, Godwine clearly suspected King Edward of paving the way for a Norman succession and may well have understood the difficulties relating to Fécamp Abbey’s peculiar status.

Earl Godwine died in 1053, but his equally powerful son continued to dominate the reign of Edward the Confessor. This was Harold Godwineson. When King Edward died childless, Earl Harold was swiftly chosen and crowned to defend the country against aggressive foreign claims. In line with his father’s policy, King Harold did not restore Steyning to the monks of Fécamp. This was hardly surprising, since there was a royal mint in the town. The manor lands were large and wealthy. Steyning was a busy port and a natural point of entry into England from Normandy. Far better for a king to have his own men at Steyning, rather than Norman monks in league with his enemies!

Unlike Duke William, King Harold neglected to send an envoy to the Pope to explain his position. By October 1066 William had landed on the south coast of England with his fleet, including a ship provided by Fécamp Abbey. The stage was set for the Battle of Hastings.

King William honoured his oath to restore Steyning to Fécamp but not entirely to the satisfaction of the abbey. It was clearly not realistic to allow an important river entry into the country to be defended by monks. The Conqueror placed William de Braose at Bramber, where the new lord built a castle and began a vigorous dispute with his neighbours at Steyning. The boundaries of Fécamp’s spiritual and secular powers were never quite reconciled with the Lords of Bramber, who had formidable powers of their own.

The practicalities of power even brought the King himself into dispute with Fécamp Abbey. The monks claimed the same freedoms in the strategic locality of Hastings as King Edward had given them at Steyning. This was more than royal generosity could allow. What’s more, William was now their king in England, not merely a duke, and Fécamp’s exalted claims were driving a wedge between himself and the Pope.

In 1088, a charter of King William’s son, Duke Robert of Normandy, restored some property in Fécamp, “which his father had in wrath taken from the abbey before the day of his death.” Even in Normandy, Fécamp’s fortunes were not at their height during William’s reign.

Technically, the Norman rule of law recognised all land tenure which exisited at the moment of King Edward’s death, since King Harold was a usurper. Due homage to King William was also required. Yet it was during Edward’s reign that Harold’s father had expelled the Norman monks of Fécamp. Were their claims valid or not and would they submit to the King? William turned his back on this embarrassing problem for nearly twenty years, but in 1085 a compromise was finally agreed. The King confirmed the abbey’s special position at Steyning but swapped the disputed property at Hastings for the Sussex manor of Bury.

From: ‘Seine Inférieure: Part 2’ Calendar of Documents Preserved in France: 918-1206 (1899), J. Horace Round (editor)

115. Charter of William, dated 1085.He confirms to the abbey of Fécamp king Edward’s gift of Steyning (Estaninges) with its appurtenances; [and] for his own part gives it gladly for the weal of king Edward’s soul, and of his own and those of Maud his wife and of his sons, with its rights and dues, sac and soc. And if the abbey did not hold that manor in the time of king Edward, yet he gives it, with all that the abbey held in Steyning in his own time. Moreover he gives and grants to the abbey the manor of Bury (Beriminstre)—for which he offered a trial and justice to abbot William and his monks, and which manor remained his – in consideration of their claim against him for their possessions in Hastings in the time of king Edward; on the terms that if that manor is worth more than the rents they had lost at Hastings, he nevertheless grants them all that manor, with its appurtenances, rights, and dues, sac and soc; while if it is not worth so much he will give compensation to the abbey for that amount.

Like every landowner in the realm, William de Braose and the Abbot of Fécamp were called to account by the compilers of the Domesday Book, completed in 1086. The process opened up a can of worms. It was found that William de Braose had built a bridge at Bramber and demanded tolls from ships travelling further along the river to the port at Steyning. The monks challenged Bramber’s right to bury its parishioners in the churchyard at Saint Nicholas. This was William de Braose’s new church, built to serve the castle but Fécamp demanded the burial fees.

King William had neglected to define the terms of his bargain with God concerning Steyning when he gave Bramber to William de Braose, so much so that the monks of Fécamp produced forged documents to defend their position. The dispute over Hastings had deprived the monks of the King’s justice until 1085. This had enabled William de Braose to gain the advantage at Bramber, over territory and rights to which he felt equally entitled. After all, he was defending a vulnerable spot on the South Coast, as instructed by his King, as well as building churches and making substantial gifts to God. In 1086 the King called his sons, barons and bishops to court to settle the issues. It took them a full day. The Abbey of Fécamp swayed the court in its favour. William de Braose was ordered to organise a mass exhumation, which must have been an unpleasant and distressing event.

Fécamp’s victory meant that Bramber’s dead were all moved to the churchyard of Saint Andrew’s in Steyning. The tolls at William de Braose’s bridge were curtailed. Fécamp also fought him and won over a park, eighteen burgage plots, a causeway, a channel to fill his moat and other encroachments onto the abbey’s land.

114. [Notification that] a plea was held at Ala Chocha a manor of William of Eu (Dou) concerning William de Braiose and the property of the abbey of the Holy Trinity [of Fécamp], King William holding the plea on a Sunday, [sitting] from morning till eve.

It was there settled and agreed as to the wood of Hamode that it should be divided through the middle, both the wood and the land in which the villeins had dwelt and which belongs to the wood; and by the king’s command a hedge (hagia) was made through the middle, and the abbey and William had their respective shares. As to St. Cuthman’s rights of burial (sepultura) it was decreed that they should remain unimpaired, and by the king’s command the bodies which had been buried at William’s church were dug up (defossa) by William’s own men, and transferred to St. Cuthman’s church for lawful burial, and Herbert the dean restored the money (denarios) he had received for burial, for wakes (wacis), for tolling the bells (signis sonatis) and all dues for the dead, swearing, by a relative in his place, that he had not received more. As to the abbey’s land which William had taken for his park, it was adjudged that the park should be destroyed, and it was destroyed. So with the warren he had made on the abbey’s land. As to the toll he took at his bridge from the abbey’s men, it was adjudged that it should not be given, as it was never given in the time of king Edward; and, by the king’s command, what had been taken in toll was restored, the tollman swearing that he had not received more. As to the ships which ascend [the river] to the port of St. Cuthman (Steyning) it was adjudged that they should be quit for twopence, ascending and descending, unless they should make another market at William’s castle. The road he had made on the abbey’s land was ordered to be destroyed, and was destroyed. The ditch he had made to bring water to the castle was ordered to be filled up, and this was done. As to the marsh, it was decreed that it should be the abbey’s (quietum) up to the hill and the saltpits. The eighteen gardens were adjudged to the abbey. The weekly toll was adjudged to the saint (St. Cuthman), saving William’s half. For all this William placed his gage (dedit cadium) in the king’s hand as being at his mercy.

From: ‘Seine Inférieure: Part 2’ Calendar of Documents Preserved in France: 918-1206 (1899), J. Horace Round (editor)

This was a momentous event in English legal history. It was the last time an English king presided personally, with his full court, to decide a matter of law. The word of this legendary monarch, William the Conqueror, might have been expected to settle matters once and for all. Far from it! The port at Steyning silted up and declined but disputes between the lords of Bramber, their own religious establishments and the church of Steyning continued for centuries. The significance of Edward the Confessor’s gift and William the Conqueror’s oath became lost in the mists of time but the legal muddle and confusion continued.