The Church Street Buildings

This is the Introduction to a booklet on sale at the Steyning Museum shop.

“Schooldays Remembered” gives a fascinating insight into life at Steyning Grammar School from as early as the 1840s. Former pupils, staff and teachers have sometimes comic but often shocking memories in a collection which reproduces their own words, selected and edited by J M Sleight.

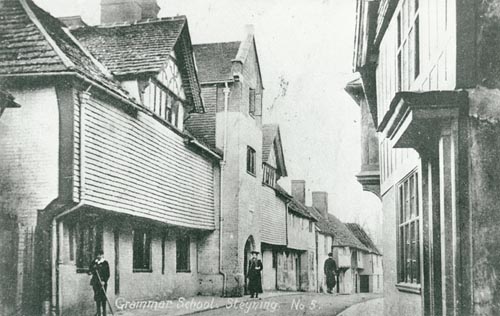

The pictures, including two held in the Steyning Museum library, illustrate these web pages only.

Brotherhood Hall was originally the Guild Hall of the Fraternity of the Holy Trinity. The original last lease of a portion of this property, granted in 1539 by the feoffees of the Fraternity, was always kept on the walls of the old schoolroom. They were: Richard Sherley, Knight, of the Wiston family; John Goffe, Tanner; William Gravesende, Mercer; John Bode, Draper; and John Edwards, Yeoman. At the Dissolution of the Monasteries all the Brotherhood property was appropriated by King Henry VIII and sold for £535 9s Id to one Henry Polsted. Brotherhood House was rented by John Gravesend in 1548 at 13s 4d p.a. The property later passed into the hands of the Bellingham family from whom it was purchased by William Holland in 1613, the year before his death.

Its use as a school for little boys can be traced back to 1584. A timber-framed I5th century construction, it has been extensively altered over the years, extended and made safe. William Holland was a merchant and Alderman of Chichester who had been born into a Steyning family of mercers. He endowed the school in 1614 with land and property in Steyning and Washington, also bought from Sir Edward Bellingham, the rents from which kept it going until the late 19th century . The school, a Free School intended for not more than 50 pupils, was administered by feoffes, or trustees, who allowed the schoolmaster to manage the whole property of 25 acres in Steyning and 7 in Washington as well as the schoolhouse and garden. He would occupy part of it, let the rest, collect the rents, keep the school buildings in repair with some of the money and use the rest himself.

The first schoolmaster in 1614 was the Rev. John Jeffrey. In 1778 the income was in the region of £27 p.a. but this had risen to over £81 by 1818, much of which ought have been, but was probably not, spent on repairs. About 1883 the land was all sold and the money invested. In 1906 the school came under the wing of West Sussex County Education Committee and new classrooms were built in 1912*, with further additions in 1933. Modern developments and alterations were carried out after the Second World War in the 1950s and 1960s to provide a new boarding house, dining room and up-to-date science laboratories. The school amalgamated with Steyning Secondary Modern School in 1968 and after a few years the Church Street site became the Lower School, a further massive rebuilding programme providing facilities for the 11 to 13 year-old age groups.

The restoration of these buildings took place in the early 1980s. It was undertaken by West Sussex County Council when the weight of the early 19th century tile-hanging threatened the jetties. Seen from the street, the ancient buildings form a Wealden ‘continuous jetty’. In the course of restoration the roof plate had to be replaced. Dendrochronological work on the timber indicated a date of 1461. At some point in the early 17th century the centre bay was sawn through and replaced with brick. Prior to this, entrance would have been by ladder. The floors were heavily sooted and there was evidence of frequent replacement; the further south one went, the more soot. In the new central brick bay stone steps led to the first floor, as now, with fire places on either side of them. By the 18th century the frontage was plastered, in the East Anglian tradition of outside plastering. The tile-hanging which caused the problems was a 19th century addition.

The old buildings in Church Street, of which Brotherhood Hall forms the focal point, have long been a source of inspiration to artists and photographers and have been reproduced many times. They have been described as a fine example of Jacobean domestic architecture, but in the past not all descriptions have been so complimentary. By 1817 the schoolhouse was apparently falling down for lack of maintenance but the schoolmaster at that time refused to allow a builder and surveyor onto the premises to estimate the cost of putting matters right. Observers from the street outside remarked that repairs had been so neglected that the buildings had fallen into a disreputable state of decay. The numbers of pupils had fallen as low as 12 whereas the proximity of the school land to the barracks, which at that time occupied the area to the east of Jarvis Lane, had boosted the master’s income from rents, very little of which had been spent on the buildings. Not surprisingly he was ‘retired’ as was his nephew who succeeded him, the latter locking the school behind him and taking the key. It was 1843 before the Trustees heard the last of him.

Meanwhile a competent new schoolmaster, George Airey, had been appointed in 1839. He had the task of rebuilding both the reputation and the dilapidations of the school. His success was remarkable – after the performance of his two predecessors he could hardly have failed to make an impression. During his long tenure he had more than just a poor tradition to contend with. There were two outbreaks of serious illness amongst the pupils, diptheria in 1859 and a disastrous epidemic of typhoid in 1861. For 30 years he had a non-stop building problem, and doubtless a perpetual financial problem to go with it.

In the School Enquiry Reports of 1867 (Taunton Commission) the inspector described the premises as: “A crazy wooden building which has been kept from falling down by well-timed repairs. No amount of money, however, spent on near-repairs would make it fit for its purpose.” Although it was ill-constructed, he said it was at least fairly furnished with desks etc. The master’ s dwelling-house was cramped and ill-adapted for the reception of boarders, while the soil immediately around the house had become very impure through improper drainage in former years. A further health-hazard lay in the unsound timber which in spite of whitewash was capable of “harbouring or generating mischief to the inhabitants”.

After Mr Airey’s death in 1877 the school was closed for rebuilding for six years. Two good rooms were added to the ground floor, with bedrooms above designed to accommodate 25 boarders. In 1883 the Reverend A. Harre was appointed Headmaster. He was soon beset with problems, not the least of which was the water supply. Water for the school came from a well which every summer ran dry. Buckets had to be filled from the town pump and there were no baths for the boys. Steyning was not connected to mains water until 1899. The boarders had to pump water up into a storage tank every Saturday. They had an unpainted metal bath in a cubby-hole (now Chatfields entrance hall) and hot water was brought in a pail. Unlimited cold water could be added from a tap.

In 1906 West Sussex Education Committee became involved in the running of the school which became part of the county secondary education system. Additions and extensions were made to the buildings, the syllabus and the number of pupils. In 1908 the alehouse owned by the Steyning Breweries, the Brewer’s Arms, was acquired for extra accommodation. By 1921 numbers had increased to 133. The school was inspected again in 1922 by which time only 15% of boys were coming from Steyning. The railway made access easy for boys from Shoreham, Lancing and Worthing. Worthing High School had not yet been built. In their Report, which focused upon the shortcomings in staff and academic performance, the inspectors did not mince their words. There would be little academic progress until large resources were made available for buildings, teachers, equipment and books. When it came to the buildings they wrote scathingly: ‘It is hard to think it could ever have been planned according to any preconceived design. The multiplicity of staircases, most of them steep and dark, the treacherous steps at various unexpected places, are more reminiscent of a dangerously constructed maze than anything else and the whole place would make a good example for storage in an architect’s museum.”