by Janet Pennington

Steyning is an ancient market town, but where was its medieval market-house? The problem seemed impossible to solve – until local historian Janet Pennington made up her mind to find the missing building. Use the numbered links in the text to view the notes for each page.

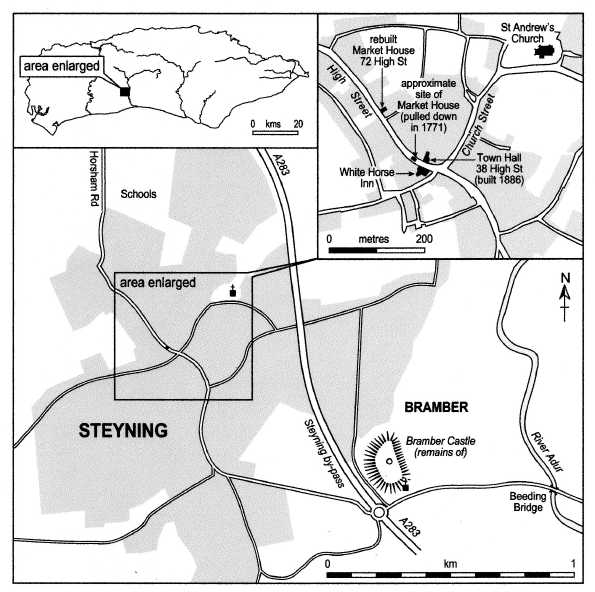

For some time Steyning’s missing market-house posed a problem: it seemed strange that a town with a market history that reached back before the Norman Conquest had no apparent trace, in physical or documentary terms, of the centrally-placed market hall so typical of other English towns. A Catalogue of the Horsham Museum Mss., however, intriguingly contained a reference to late-eighteenth century papers containing ‘much detail about Steyning Town Hall’. Since a Town Hall at 38 High Street was built in 1886, in the late-nineteenth century, it was not clear what this other building could be. Thus Steyning’s ‘lost’ market-house or ‘Town Hall’ was revealed. Anna Butler had referred to it briefly in her book on Steyning published c.1913 with no sources listed, but her statement had later been discounted as an error.1

‘From time immemorial until the year 1771 the Town Hall or Market House of Steyning Stood in the Middle of the High Street there.’

Horsham Museum (hereafter HM) Ms.126A. Incidentally, from 1291 ‘time immemorial’ or ‘time out of mind’ was time beyond legal memory, fixed as the period before the accession of Richard I in 1189.

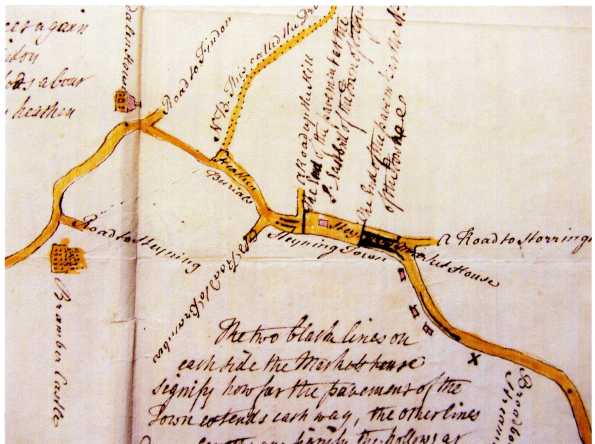

Until 1771 Steyning had a market-house standing in the middle of the High Street, not far from the crossroads by the White Horse inn (Fig. 1). A sketch map of Steyning dated 1763 shows its approximate position (Fig. 2). From documentary evidence in rentals it can be deduced that it stood between the present Post Office (44 High Street) and Lashmars (31 High Street). The sketch map shows it not quite centrally placed, but slightly to the south-east side of the street. Harris finds that market halls were usually placed off-centre, nearer to one side of the street or even in the corner of the market area.2 Steyning’s market-house was in the middle of the market area surrounded by inns. In the 17th century the Swan (later the George) and the Spread Eagle (later the King’s Arms) stood on the north side of the road, with the Chequer, the Blue Anchor, the Crown and the White Horse on the south.3

As a borough Steyning had the right to hold a market and one existed at the time of Edward the Confessor. After the Norman Conquest the Abbot of Fécamp claimed the weekly market tolls. In 1288 it is documented that William le Veske of Steyning had built four shops in the middle of the market ‘in the King’s highway’ and that they were a nuisance to the inhabitants. William’s wife Joan was using two of these shops herself. The Sheriff was commanded by the local court to pull them down, but it may not have happened. Richard le Veske was a Member of Parliament for Steyning in 1311 and 1314, and the family would have had influence in the town.4

From merchants taking matters into their own hands and building ‘island units’ that began as portable stalls but gradually became ‘fixed’, larger and more permanent buildings were erected in the midst of all the horse and wheeled traffic, profiting from their central siting in the bustle of the market area, usually with inns on either side. Whether William le Veske’s shops turned themselves into a bona fide market-house is unknown, but this was sometimes the way that market-houses came to be positioned in the middle of a town’s main street. The town’s officers may have decided to erect a proper market-house, with space for stalls in the open ground floor, perhaps at some time in the 14th or 15th centuries. Some of the earliest in England to survive were built in the late-15th and early-16th centuries.5

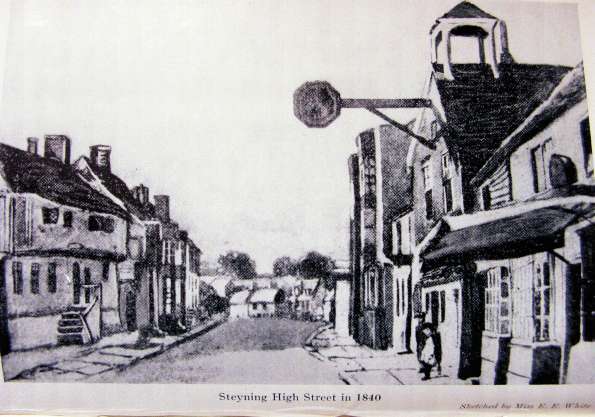

In August 1655, when Quakers George Fox and Alexander Parker came to the town, they were received by the town constable, John Blackfan, who ‘… Lett them have the Liberty of the Market-house to meet in.’ Blackfan himself became a Quaker and some of his family, with other Sussex men, emigrated with William Penn in 1682. So the first Quaker meeting in Steyning must be imagined, not at the present market-house at 72 High Street (Fig. 3), but in the first floor room of the earlier building that stood in the middle of the street towards the White Horse area of the town. A notice fixed to the front of today’s ‘Old Market House’ reads: ‘George Fox, Founder of the Society of Friends, (The Quakers) Held A Meeting Here in 1655 (Sussex Archaeological Collections Vol. 55)’, the SAC reference lending credence to the statement.6

The earlier market-house had a:

… large Upper Room and beneath was the Dungeon or Cage, and Stocks. In the upper part of the Building was a large Clock, the Bell of which, besides the purpose it had of giving the Hours, used whenever Divine Service was performed at the parish Church (which stands at a Considerable Distance from the High Street) to be Tolled by the parish Clerk by way of Notice to the Inhabitants.

HM, Ms. 126A.

In the eighteenth century the building was often referred to as the ‘Market House or Town Hall’. Many similar market halls still survive in country towns all over England. Great Bedwyn’s ‘old town hall’ in Wiltshire gives some idea of the type that Steyning might have had, though perhaps without a chimney, and some timber-framing may have been visible (Fig. 4). Great Bedwyn’s lock-up can be seen, and the bell-housing is similar to the one on Steyning’s later market-house before a new clock turret was added in 1848-9 (Fig. 5).7 Titchfield Market Hall, at the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum, Singleton, can also be used as a comparison (Fig. 6).8

The ground floor of Steyning’s old market-house would have been open for a large part of its area, with the end behind the stairs taken up by the town gaol – often called a cage or dungeon. This was probably boarded up to breast height, with perpendicular wooden bars above. The stocks were also in full view of the town’s inhabitants. By 1771 the building had become a problem. It was ‘… in a Ruinous State and (standing in the Middle of the principle Street [sic.]) a Considerable obstruction and Inconvenience to the public and Inhab[itan]ts of the place …’9

Surgeon Richard Penfold, variously referred to as ‘Mister’ or ‘Doctor’, was the agent of the Honeywood family who owned many Steyning properties. Penfold proposed that the old building be pulled down and a new market-house erected on the site of a house owned by Sir John Honeywood. Honeywood and the Duke of Norfolk were normally only interested in Steyning properties in order to promote their own candidates as Members of Parliament. The Duke of Norfolk was Lord of the Manor, and between 1798 and 1799 he acquired c. 80 properties in the town, having come to an agreement with his rival in 1794 that they would share the votes, after two recent disputed elections. Steyning was one of the many ‘Rotten Boroughs’ in the country that profited from corrupt voting practices in the parliamentary elections. Votes in the town were attached to houses built on old foundations and until the 1832 Reform Act voting was usually a matter of who lived where and who paid what to whom.10

Local politics were not the only problem. It can be seen that nearly ten years earlier Richard Penfold had been in correspondence with Mr. Parham, Attorney at Law in Horsham, over the matter of the market-house and a new Turnpike Act.11 He wrote on 30 December 1763 thanking Parham for a copy of the preamble to the Bill, indicating that he wanted some changes made regarding the pavements in the High Street. He mentioned the plan which showed ‘… two black lines drawn across on each side the Market House as the end of the pavement at each hollow way …’ (Fig. 2). Four years later, on l December 1767 he was still writing to Parham, requesting that the pavement of the town might be included in the new road, as it would be much better for everyone. He continued that ‘… we likewise could wish to have leave to remove the Markett House to any commodious place of the Town that the major part of the Inhabitants shall think proper …’ though nothing was said about its being in a ruinous condition then. Penfold kept Sir John Honeywood informed of his views and sent him a copy of the plan.12

It was noted in 1771 that the town constable (a different inhabitant was appointed annually) generally let the upper room of the market-house for one guinea (£1.05) to whomsoever provided stalls or standings at Steyning Fair each year.13 The person who looked after the clock had a key to the room, and handed it over whenever the Parish Clerk needed it. So several people were involved in the administration of the building. While various inhabitants were agitating about the fate of the apparently ruinous market-house, Edward Young (town constable in 1771) was passing along the High Street and saw Andrews, who normally looked after the clock, pulling down the bell. He asked what was going on and who had given him authority for such action. Andrews replied that Mr. Penfold had done so. Hearing this, Young damned both Mr. Penfold and Andrews, saying that nobody had the right to touch the market-house without his authority. Andrews stopped what he was doing and hurried away to let Mr. Penfold know that the constable was very angry.14

Penfold took quick and tactful action, going round to some of the inhabitants, and particularly to constable Edward Young to gain his consent for the taking down of the market-house. In this he succeeded as ‘… Soon after w[hi]ch it was accordingly pulled down and with the old Timber and Mat[eria]ls the present Town Hall or Market House was Erected upon the Scite of a House [at 72 High Street] then belonging to S[i]r John Honeywood which was held … of the Duke of Norfolk as Lord of the Boro’ …’ (Fig. 3). These two landowners both had an interest in the building and its site.15

Everyone seemed pleased with the outcome. The obstruction to the High Street had been removed, which would help the traffic coming down a possible new Turnpike road, and a new market-house had been built with the timber and other materials salvaged from the old. ‘The Town Clock and Bell were also removed from the Old Building and Replaced in that newly erected. The Dungeon or Cage and Stocks were fix’d in the lower part …’ It was agreed that the room above ‘… being more neat and decent than the old one …’ would be kept locked by the succeeding constables and not let out as before, though this did not happen (see below).16 The parish authorities wanted to keep the room in a fit and proper state for the manorial courts that were held from time to time, and also for electioneering purposes, or any other public need.

The town fire engine was put in the lock-up (and presumably removed when the space was needed for miscreants) and it was agreed that the constable would have the keys, could let the lower part of the new building, and use it for the display of earthenware and other goods for sale at the Fairs. There was also the problem of ‘His Majesty’s Troops’ who had by custom been allowed to deposit their baggage in the Upper Room of the old market-house when they were quartered in, or marching through, the town. The new upper room had to be kept clear for this purpose too. The old clock was re-erected and can be seen hanging out over the High Street on the end of a timber support; the bell can also just be glimpsed in the turret (Fig. 5). Between 1827 and 1840 the Duke of Norfolk presented the town with a clock which struck the hours. A new turret was built for it in 1848-9 and the old bell was presumably removed (Fig. 3).17

On 31st July 1771 a jolly scene can be envisaged, as an account of Steyning grocer and builder Daniel Easton, who supplied men for the work, shows 9s. paid for ‘Beer at Rearing the Market House’.18 This would have been a celebration after the successful erection of the timber-framing which can be seen today within the present building at 72 High Street, particularly on the first-floor landing and in the room overlooking the street (Fig. 7). Whether most of the timber came from the old market-house or whether some came from the building that formerly stood on the new site is unknown. Just over a month later, on 3 September, there was more ‘Beer for the men’, as well as beer for Mr. Penfold, Peckham and ‘myself’ (presumably Easton the builder).19 This was probably for the ‘topping out’ ceremony. Nine years later, in 1780, the windows needed mending and in 1788 a new pair of town stocks was made by carpenter John Streeter, who also put new locks on the dungeon door.20

It might be thought that that was the end of the story – the old market-house pulled down, a new one erected at reasonable cost thanks to the recycling of timber and other materials. But no…

Some time after the rebuilding, the possibility of moving the ‘Sussex Epiphany Sessions’ (the January Quarter Sessions) from Midhurst to Steyning was discussed. County Magistrates wanted to view the ‘new’ market-house to see whether it was fit for the purpose. The constable, Tilly, gave notice to four Steyning inhabitants to remove goods they had deposited there. Despite all the good intentions originally of keeping it clear, the constables had presumably seized the opportunity to raise some cash. Cozens, Easton and Read ‘… immediately removed their goods but … [Joseph Curtis] who had four or five pieces of Old Cables Cut in Lengths and some small Old Rope positively refused to take the same away …’ So Tilly, assisted by Edward Young, the former constable, threw it all out of the window and into the High Street. Tilly sent his servant William Dumbrell to Curtis’s house to tell him what had happened, asking him to clear the mess from the street, which he did in about half an hour.21

This does not sound too alarming, but it is not the whole story – in the subsequent Court Case at the East Grinstead Assizes in March 1790 it becomes clear that far more than some old cable and rope belonging to Curtis had been hurled out of the window. The Duke of Norfolk and Sir John Honeywood (the latter the grandson and heir of his namesake who had died in 1781) were also at odds over electioneering practices in Steyning.22 Sir John brought the action to show that he had exclusive rights to the market-house, but the Duke of Norfolk’s lawyer, Mr. Medwin of Horsham, acting for Joseph Curtis on behalf of the Duke of Norfolk, describes in his brief just what Tilly and Young had done with his client’s belongings:

… with force and Arms [they] Seized and took possession of divers Goods and Chattles (to wit) Ten Cart Loads of Wood, 200 lb weight of Hemp, 500 Ropes, 200 Sacks, 50 Chairs, 50 Tables, 50 Stools, 200 Dressed Hides, 200 Undressed Hides, 20 Beds, 20 Bedsteads, 20 Bed Curtains, 20 Blankets, 20 Pillow, 20 pair of Sheets and 20 Coverlids of the s[ai]d P[lainan]t (£500 value) in the room of the Market House … and then with great force and Violence Tossed, Hurled Cas’t and Flung the s[ai]d Goods and Chattles … from and out of the room into the public and open Street … and thereby then and there greatly dirtied spoiled and damaged the same and rendered them of little use or value …

HM, Mss. 126A; 126.2.10.

Apart from the underlying antagonism between Sir John Honeywood and the Duke of Norfolk, and allowing for a little written exaggeration, it would seem that Curtis had a case, though he had surely rather overfilled the upper room of the new market-house with his goods. It is approximately 34′ 6” (c. 10.5 m) long by 16′ 8” (c. 5.0 m) wide. Amongst the surviving documentation relating to the case there are some bills for food and drink during the court case. The lawyers and witnesses stayed at the Swan Inn at East Grinstead, taking breakfast, tea and dinner, as well as imbibing gin, punch and French brandy. A special jury was called; 48 names were submitted to begin with, all Sussex gentry. It is clear that those known to be siding with either Sir John Honeywood or the Duke of Norfolk were removed from the list. Twenty-four presumably non-partisan jurors were finally sworn in and at least 11 Steyning inhabitants were called as witnesses to give evidence.23

The defendants, Tilly and Young (the Honeywood interest), were found not guilty. They had been justified in removing Curtis’ goods after having given notice and receiving his refusal. However, Curtis (the Duke of Norfolk interest) was awarded £500 to cover his spoiled property, presumably to be paid by Honeywood. Mr. Medwin, the lawyer for Curtis, submitted a bill to the Duke for a year’s fees for working on the case, amounting to approximately £193; it had been an expensive business for everyone involved.24

Steyning’s eighteenth-century market-house is quite a feature of the town. The Duke of Norfolk’s clock rings out the hours and the bell can be heard from far afield. It once struck more than 300 chimes instead of ten, and occasionally the three faces of the clock all show different times.25 While no Quakers met in the upper room in 1655, as stated at present in notices both inside and outside the building, the riotous scenes that did occur there over 130 years later have led indirectly to the building in which they did meet – Steyning’s ‘lost’ market-house.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for help from the following people: to Sue Rowland who drew the maps for Fig. 1; to John Townsend for alerting me to the 1763 sketch map at the West Sussex Record Office; to Kim Leslie of WSRO for information on the date of the Turnpike Act; to Chris Tod, curator of Steyning Museum, for information and advice and to Jeremy Knight, Curator of Horsham Museum, for help with locating documents and for his hospitality and also to Barbara Dickson, formerly of 72 High Street, who allowed me full access to the building.

Postscript by Janet Pennington

Due to research I have been doing on the former Swan/George/King’s Head Inn at what is now 46-52 High Street, I can more accurately locate the market-house between that range of buildings (more or less the present fishmonger’s shop) on the NW side and numbers 33-35 on the SE side.

- S.G.H. Freeth, I.A. Mason, P.M.Wilkinson, A Catalogue of the Horsham Museum MSS, (Chichester: West Sussex County Council, 1995), 19;. A. Butler, Steyning, Sussex: The history of Steyning and Its church from 700-1913, (c.1913), 27: ‘The old Session House or Town Hall, which stood in the middle of High Street, and in which the Courts of the Lords were held, was removed years ago…’; with thanks to Chris Tod, Curator of Steyning Museum, for making this book available – the two copies that should be in Steyning Library have disappeared; T.P. Hudson, The Victoria History of the County of Sussex, 6, pt 1, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 238, f.n.13; ‘Butler, Steyning, 27, incorrectly states that the town hall formerly stood in the middle of High Street’. However, Butler was right, the town hall or market-house (my italics) did stand in the middle of the High Street. ↩︎

- R. Harris, (ed.), Weald & Downland Open Air Museum Guidebook, (1988), 17. ↩︎

- WSRO, Add. MS. 37,522. Church Street (which should be opposite ‘A Road up the Hill’) has not been indicated, presumably because the map was drawn for consideration of a turnpike road through the town; West Sussex Record Office (hereafter WSRO), Wiston Mss 6152-3; 6964, 6972-7: these rentals list a house on the north side of the High Street ‘on the north side of the Market-house’; WSRO, Add. Ms. 22,157 lists a house on the south side of the High Street in 1683 that is ‘against the market-house there’. The word ‘against’ did not then mean ‘next to’ as nowadays, but ‘directly opposite, facing, in front of, in full view of’; J. Pennington, ‘The Inns and Taverns of Western Sussex, 1550-1700: A Regional Study of Their Architectural and Social History, (unpub. PhD, University of Southampton, 2003) p.16, table 4 (copy of thesis in SAS Library). ↩︎

- Hudson, 234-5; E. W. Cox and F. Duke, In and Around Steyning: A Historical Survey Made In 1953, (Steyning: Wests, 1954), 85; see R. McKinley, The Surnames of Sussex, (Oxford: Leopard’s Head Press, 1988), 164-5 for a history of the surname Veske; E. W. Cox, ‘The Steyning Burgesses 1278-1826’, Steyning Parish Magazine, 115, (July, 1929), 2. ↩︎

- Harris, 17-18. ↩︎

- W. Figg, ‘Extracts From Documents Illustrative of the Sufferings of The Quakers in Lewes’, Sussex Archaeological Collections, (hereafter SAC) 16, (1864), 72-73; Cox and Duke, 85-86, but they have wrongly assumed that the meeting was held at the present market-house, 72 High Street; P. Lucas, ‘Some Notes On The Early Sussex Quaker Registers’, SAC, 55, (1912), 85-87. It is hoped that this statement may shortly be amended. ↩︎

- J. Brown, The English Market Town: A Social and Economic History 1750-1914, (Marlborough: The Crowood Press, 1986), 122, illustration of the old town hall at Great Bedwyn, Wiltshire. ↩︎

- Harris, 17-18. ↩︎

- HM, Ms. 126A. ↩︎

- ↩︎

- He is presumably referring to what was to became the 1764 Turnpike Act for the road between Horsham and Steyning, though the improvements were not made for some years. ↩︎

- WSRO, Add. Ms. 37,521-2. ↩︎

- Hudson, 234, notes three Fairs in Steyning, on 8th September, Michaelmas, and 29th May. ↩︎

- HM, Ms. 126A. ↩︎

- HM, Ms. 126A. ↩︎

- HM, Ms. 126A. ↩︎

- J. Pennington, The Chequer Inn, Steyning: Five centuries of innkeeping in a Sussex Market Town, (Lancing: Lancing Press, 1990), 27, notes that in the early 19th century there were ‘Girls in the Cage’ during the time that soldiers were garrisoned in Steyning during the Napoleonic Wars; in 1815 one man was kept ‘in hold’ at the Chequer Inn for two days, though quite where he was kept is unknown, hopefully not the cellar; Hudson, 13-14, 238; the former pigeon house of Michelgrove House at Clapham had been converted into a clock-tower some time after 1800. The Duke of Norfolk purchased the estate in 1827 and eventually pulled the house down, when the clock became redundant and was moved to Steyning. ↩︎

- WSRO, Add. Ms. 45,501, Bill of Thomas Griffin to Daniel Easton. ↩︎

- WSRO, Add. Ms. 45,501, Bill of Thomas Griffin to Daniel Easton. ↩︎

- HM, Ms. 126A. ↩︎

- HM, Ms. 126A. ↩︎

- Hudson, 240; W. A. Barron, ‘Sidelights on Election Methods in the Eighteenth Century’, Sussex County Magazine, 24, no.3, (24 March 1950), 77-80; HM, Ms. 126A reveals that Curtis was an elector in the Honeywood interest, while Tilly and Young espoused the interest of the two candidates put forward by the Duke of Norfolk. ↩︎

- HM, Mss. 126A; 126.2.2; 126.2.8; 126.2.9. ↩︎

- HM, Mss. 126A; 126.2.11; 126.2.12; 126.2.13; 126.2.19. ↩︎

- West Sussex County Times, 19 October 1956. ↩︎