Chance Memory

I can’t forget the lane that goes from Steyning to the Ring

In summer time, and on the Down how larks and linnets sing

High in the sun. The wind comes off the sea, and Oh the air!

I never knew till now that life in old days was so fair.

But now I know it in this filthy rat infested ditch

When every shell may spare or kill – and God alone knows which.

And I am made a beast of prey, and this trench is my lair.

My God! I never knew till now that those days were so fair.

So we assault in half an hour, and, – it’s a silly thing –

I can’t forget the narrow lane to Chanctonbury Ring.

This poem has haunted many people since it was first printed by the Daily News on 23rd June 1916. The name of the poet was given as Philip Johnson. The fate of this man, who turned to poetry half an hour before ‘going over the top’ to face the guns of World War I, was unknown for over fifty years. Did he survive?

The poem appears in several war poetry anthologies and accounts of life in the trenches. It was treasured by local people, of course, but particularly by survivors of the 24th Division of the British Army. These were the Kitchener Boys who responded to the famous posters showing the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, with his enormous moustache and pointing finger. The carnage of this war was already taking its toll of professional troops and so the next wave would be the volunteers, before conscription was introduced.

On a rainy Saturday in September 1914, several hundred young men began to arrive at Shoreham-by-Sea railway station in West Sussex, to the utter astonishment of local residents. The men were volunteers from all parts of the country, most without uniforms, wet, hungry and cold. The camps set up in Buckingham Park and extending across the back of Shoreham to Slonk Hill, were nowhere near ready with tents and supplies for the twenty thousand who arrived in the following days. Local people soon caught the patriotic spirit of their unexpected visitors and welcomed the volunteers into their homes. The young men were eventually distributed into camps and houses from Brighton to Worthing. Training included brisk marches across the Downs and mock assaults on scenic local hilltops such as Chanctonbury Ring, Cissbury Ring or Lancing Ring.

These events were described in The Story of Shoreham by Henry Cheal, published in 1921. He captured something of the heady excitement of the youthful volunteers, many still teenagers, and local people alike. The nine months when Kitchener’s Boys were marching and singing the latest songs through the streets and downland tracks, handing bread over the camp fences to children and falling in love with local girls, were the happiest of times. The contrast with what was to come could not have been more stark. The sentiments of the Steyning poem, quoted of course by Henry Cheal, were felt instinctively and intensely by these men. Nostalgia for the innocence, joy and optimism of that paradise lost could all be conveyed by the mere mention of a Sussex downland scene or a local place-name.

The volunteers left Shoreham in June 1915 for Aldershot in Surrey, where they trained with guns for the first time before departing to the Western Front in August. They had no period of grace before the devastating sacrifices began at Loos. At Shoreham, a large contingent of the Canadian army moved in to enjoy the same idyllic respite before departing for war.

The author Ernest Raymond (1888-1974) was deeply affected by the Steyning poem. In his autobiography published in 1970, Good Morning, Good People, he revealed a remarkable piece of information. The passage is worth quoting in full:

In 1916, having recently escaped from the mud and filth of Gallipoli, I was with my brigade in the Sinai Desert, where we were slowly laying a railway through the sands towards Gaza, making straight in the desert a highway to Jerusalem. And one day I chance upon an old tattered copy of the Daily News and read in it a brief poem, whose final couplet seemed to me – I have said this in articles and on platforms and in private talks for over half a century – to capture an English soldier’s native patriotism with simpler or more perfect words than any other lines in that luxuriant yield of poetry which sprang from the First World War. Ever a lover of the bare, sweeping downs of Sussex which find their crown in the ring of noble trees on Chanctonbury, I was caught, I suppose, by the title From Steyning to the Ring. I read the poem once – twice or thrice maybe – and have been word-perfect in it ever since. It was printed over the name ‘Philip Johnson’, and never from that day in 1916 till two mornings ago, in 1969, fifty-three years later, have I known who ‘Philip Johnson’ was, or heard of him.

I know now. The writer of the poem was a young officer in the 5th Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment serving in France, and this was his poem.

I can’t forget the lane that goes from Steyning to the Ring

In summer time, and on the downs how larks and linnets sing

High in the sun. The wind comes off the sea, and oh, the air!

I never knew till now that life in old days was so fair.

But now I know it in this filthy rat-infested ditch,

Where every shell must kill or spare, and God alone knows which.

And I am made a beast of prey, and this trench is my lair –

My God, I never knew till now that those days were so fair,

And we assault in half-an-hour, and it’s a silly thing:

I can’t forget the lane that goes from Steyning to the Ring.

I don’t know how many times I’ve walked up that lane quoting this last couplet to those walking with me, or how often I have mentioned on platforms and in articles the whole magical little poem by an author unknown.

And two days ago there comes a letter from a Miss Purvis, saying,

Since the death of my brother, Canon J.S. Purvis, in December I have been searching the family news cuttings albums to find an article which you wrote in the Sunday Times of 22nd May 1927. My mother preserved our copy at the time for she knew the pen name Philip Johnson was that of her elder son John Stanley. Through the years I have often thought that I should like to reveal to you the real name of the author who wrote this poem.

The words were sent without my brother’s knowledge to the Press by his friend, a Quaker doctor, serving with the Red Cross. Please forgive me if I have bored you with these reminiscences but I have always wanted to uncover the anonymity of my noble brother ‘Philip Johnson’ and to thank you for the words in your article which gave so much pleasure to my mother and to me.

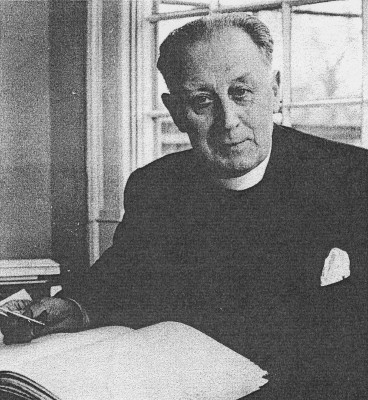

So ‘Philip Johnson’ was really John Stanley Purvis who became Canon Purvis of York and internationally famous for his versions of the York mystery plays. He died last year, 1968, and at his Memorial Service in York Minster the Dean said, ‘We are met to give thanks to God for the life and work of John Stanley Purvis, Canon of the Cathedral Church, a Yorkshireman whose faithful Christian witness and devoted scholarship have enriched the hearts and minds of many in this County and beyond it.’

The Quaker friend of John Stanley Purvis obviously chose the Daily News because it was a pacifist newspaper, owned by the Quaker George Cadbury. Quakers, many of whom were members of the Union of Democratic Control anti-war party, were often attacked, persecuted and imprisoned during the Great War. As conscientious objectors, it was common for Quakers to serve in the Red Cross. Whoever invented the pen name Philip Johnson to disguise the identity of a serving officer was taking a sensible precaution.

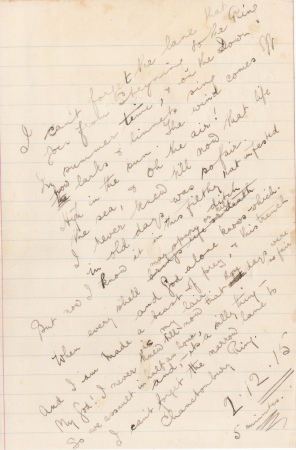

The version of the poem given by Ernest Raymond varies a little from the one which we now know is the author’s original, dated December 2, 1915. Remarkably, Steyning Museum has acquired the hand written and dated original. It shows, in particular, the final line as, “I can’t forget the narrow lane to Chanctonbury Ring.”

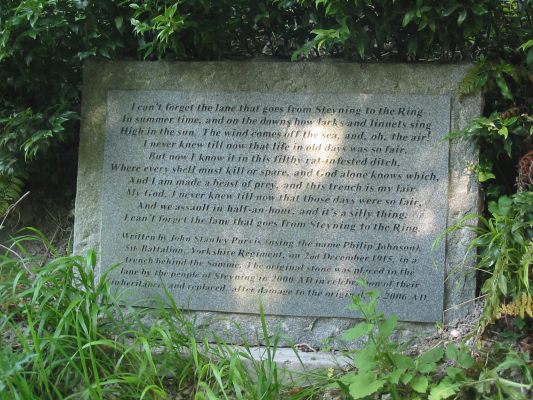

The Ernest Raymond version was carved into Yorkshire stone and mounted in that narrow Steyning lane, Mouse Lane, in the year 2000. The unveiling ceremony took place on Saturday, December 2nd, exactly 85 years after John Stanley Purvis wrote it. Councillor George Cockman said in a booklet produced for the event:

I have a sense that this stone will become a landmark, held in affection by local people and visitors alike. Like John Purvis who thankfully was able to walk this lane before and after the war, the downs, and Chanctonbury in particular, continue to attract and delight hundreds of people every year. Many, I believe, will take the ancient driftway down through the beech woods to find this stone at its end, and finding it will be enriched by the tradition of affection for downs, lane and town which John Purvis so memorably captured on that battlefield. And they will be glad that in the millennium year, we played our part in enshrining that tradition by setting this stone and telling its story.

In 2006, a lorry backed into the stone and split it in two. The local sponsors were concerned and generous enough to have a new one carved and mounted in the same spot. The cracked version was mounted next to the entrance of Steyning Museum, so there are now two stones commemorating the Steyning poem.

There is another poem by ‘Philip Johnson’ or ‘Johnstone’. It was first published in The Nation magazine on February 16th, 1918, nine months before the war ended. There has long been doubt that High Wood is the work of J.S. Purvis. There is circumstantial evidence, however. The initials PJ are, of course, the reverse of JP for John Purvis. He was literally John’s son or Johnson, since his father’s name was John Bowlt Purvis. Also, the records of the 5th Battalion Yorkshire Regiment show that 2/Lt J.S. Purvis was injured on September 15, 1916 during the final assault on High Wood. A regimental history, The Green Howards in the Great War, by Colonel H.C. Wylly, originally published in 1926, gave an account of this and concluded:

The 5th Battalion The Green Howards with the 4th, reached its objectives and clung to it under a very heavy shelling, but when relieved early on the morning of the 19th by a brigade of the 23rd Division and withdrawn into divisional reserve, the 5th had had four officers and forty-eight other ranks killed, eleven officers and one hundred and sixty-two NCOs and men wounded and twenty-seven men missing – a total of two hundred and fifty-two casualties.

The names of the officer casualties are: killed, Lt-Col J. Mortimer, CMG, Capt F. Woodcock, 2/Lts G.S. Phillips and W.R. Lowson; while the wounded were Capt H. Brown, DSO, MC, Lts E.M. Robson and G. Harker, 2/Lts P.H. Sykes, A.G. Winterbottom, C. Martin, C.R. Hurworth, C.H. Dell, W.H. Game, W. Rennison and J.S. Purvis.

High Wood

Ladies and gentlemen, this is High Wood,

Called by the French, Bois des Fourneaux,

The famous spot which in Nineteen-Sixteen,

July, August and September was the scene

Of long and bitterly contested strife,

By reason of its High commanding site.

Observe the effect of shell-fire in the trees

Standing and fallen; here is wire; this trench

For months inhabited, twelve times changed hands;

(They soon fall in), used later as a grave.

It has been said on good authority

That in the fighting for this patch of wood

Were killed somewhere above eight thousand men,

Of whom the greater part were buried here,

This mound on which you stand being…

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Madame, please,

You are requested kindly not to touch

Or take away the Company’s property

As souvenirs; you’ll find we have on sale

A large variety, all guaranteed.

As I was saying, all is as it was,

This is an unknown British officer,

The tunic having lately rotted off.

Please follow me – this way…

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . the path, sir, please,

The ground which was secured at great expense

The Company keeps absolutely untouched,

And in that dug-out (genuine) we provide

Refreshments at a reasonable rate.

You are requested not to leave about

Paper, or ginger-beer bottles, or orange-peel,

There are waste-paper baskets at the gate.

Purvis was a teacher and he visited his school at Cranleigh in Surrey during a period of convalescence after the horrors of High Wood. The Cranleighan termly school magazine of March 1917 reported that, “Mr. Purvis, who was invalided home suffering from shell shock, has recovered, and has returned to the front.”

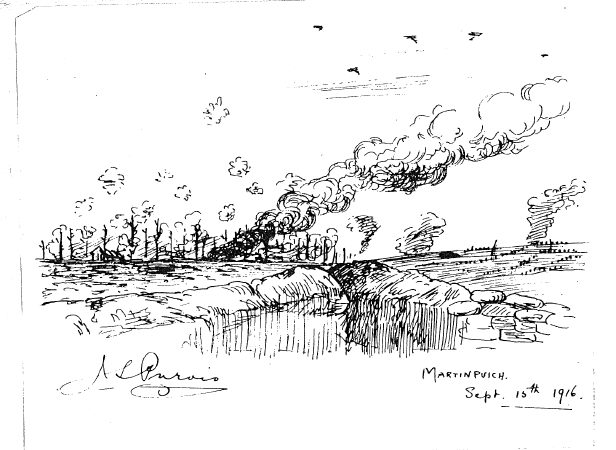

In July 1917, there was an article from Purvis printed in The Cranleighan. His Impressions of the Battlefield appears to give a remarkable eye witness account from his besieged location at High Wood. In addition, the school archives kindly provided Steyning Museum with a copy of a sketch of Martinpuich, visible from High Wood, signed by Purvis and dated September 15th, 1916. His more extensive battlefield sketch book is held by the regimental archives at the Green Howards Museum in Richmond, Yorkshire.

Raymond Asquith, son of the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, died in action on September 15th, 1916. The historic first use of British tanks in battle took place on this memorable day, which Purvis was able to watch from his vantage point at High Wood. The tanks raised British spirits and astounded everyone who saw them advance, although it was some time before the army developed the effective use of tanks in formation to lead an attack. A cavalry charge and surveillance aircraft also appeared at High Wood, demonstrating the transitional state of warfare in which nothing could yet break the long and lethal stalemate.

The seventy-five acres of High Wood really was one of the first battle grounds to be visited by tourists, though it was the appropriation of battle sites for profit which was the target of the poem. At that early date, the poet was correct to suggest that there were some eight thousand British and German soldiers killed at High Wood who remain there today. There is still so much live ammunition that it is unsafe to stray from the paths. The battle for High Wood lasted sixty-four days, with little respite until it was taken by the British. For his catastrophic errors and the “wanton waste of men”, Major-General Charles Barter was relieved of his duties.

Elspeth Johnstone wrote about the poem High Wood for the centenary of the Battle of the Somme in The Western Front Association magazine, Stand To! (number 106). In the article entitled ‘The Man behind a Poem for Today’ she also researched the career of the recently comfirmed poet. Of his two known poems, she wrote:

The first, Chance Memory, before he went to the front, is written in the pastoral style of the period. The second, High Wood, was written by a man who had seen and suffered the worst afflictions life could mete out, even though he hid the horror and hideousness with satirical humour. It was very much in the style of poetry and writings found in the The Wipers Times, the wartime trench magazine.

High Wood can still prick the conscience of a battlefield tour guide today, although Elspeth Johnstone concluded her article with a less bleak observation than the poem:

High Wood is private property and fenced off, but there are three memorials outside its perimeter. What Purvis may not have foreseen was the deep respect that is paid by both the young and the old who visit the Somme one hundred years on and stand outside his wood ‘….Of long and bitterly contested strife’.

John Stanley Purvis was second in command of a trench mortar battery and an acting Lieutenant when he suffered another tragedy in June 1917. His brother George Bell Purvis was killed in action. Probably on compassionate grounds, he was seconded to the Bomb and Trench Mortar School as an assistant instructor, where he was promoted to Lieutenant in September 1917. He returned to his regiment in March 1918 and relinquished his commission on account of ill-health the day after Armistice Day. Lieutenant Purvis was fortunate to have survived the war. He faced great danger from March 1916 when he became a newly assigned Second Lieutenant. This is commonly said to have been the rank least likely to survive.

A mystery surrounds the Steyning poem. Purvis reached the Western Front after the date on which he wrote it. On December 2nd, 1915 he was still a teacher at Cranleigh School, Surrey and a Second Lieutenant for the Junior Division of the Officers Training Corps. The record of Purvis’ service medals confirms that he was not in active service in December 1915, since he did not receive the 1914-15 Star. This medal was issued to everyone who saw service in a theatre of war between 5th August 1914 and 31st December 1915. In addition, his school magazine, The Cranleighan, recorded in March 1916 that “2nd Lieut J S Purvis, who left us at the end of last term, is about to be attached to the 3/5th Yorks Regiment”. The end of term before Christmas 1915 was 17th December.

The story was confirmed in 2009 by the marvellous discovery of more poems by Purvis. They were hand-written in a notebook archived at the Borthwick Institute in York. One of these poems was dated December 1st, 1915, the day before Chance Memory was written and the location was specified as Cranleigh. Significantly, High Wood also appeared in the collection, and so the authorship of this poem is no longer in doubt. The notebook, entitled Verses and Fragments, was published by the Borthwick in 2023. There are many more poems to treasure in this collection.

Chance Memory has rightly taken its place alongside the work of Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon and others still known as the War Poets. Many people who love Chance Memory are convinced that it could only have been written by someone who had personal experience of the trenches. But Chance Memory was the poet’s imagined moment of facing death. It was a thought shared by millions like him. The idea which has so enthralled readers, of a man writing poetry half an hour before ‘going over the top’, was perhaps always improbable.

Another interesting entry in The Cranleighan school magazine suggests that Chance Memory does record one real event. The poem may have been provoked by thoughts of a trip to Chanctonbury Ring on March 25th, 1914. An Officers’ Training Corps entry reported:

Cranleigh School OTC and St John’s, Hurstpierpoint, OTC, defended Chanctonbury Ring against Christ’s Hospital OTC.

The Cranleighan of July 1915 also noted that Purvis had trained with his regiment in Newcastle during the Easter holidays that year, after which an article described in detail, with a diagram, his newly designed trench system for the training of Cranleigh OTC.

Purvis returned to Cranleigh School after the war. His job as a teacher of history was still there for him. He had joined the school in September, 1913 after studying at St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge. There is even today a thriving Purvis Society at Cranleigh. He had gained his MA in Classics and History and, pursuing a lifelong enthusiasm for his subject, he became an active member and Honorary Archivist of the Surrey Archaeological Society. The Cranleigh School archive records that Purvis’ hobbies included sketching and water colour painting, and he was a keen horseman. This may provide a further clue as to why he adopted the pen name Philip, originally a Greek name meaning ‘lover of horses’.

The school teacher and amateur historian had a further career in mind, however. He was ordained in 1933. Leaving Cranleigh in 1938, he returned to his native Yorkshire where his career in the Church soon presented him with marvellous opportunities for a historian. He was appointed as the archivist to the Archbishop and Diocese of York in 1939 and rose to become a Canon of York Minster. Purvis developed the York archive to establish the city as an academic centre and placed it in the care of the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research in 1953 as its founder and first director. The project was key to the creation of York University in 1963. The Yorkshire Post of May 11th, 2007 reported that the archive’s two million documents were about to be placed in an online database:

Basic indexes were created by the institute’s former head, Canon John Purvis, but much of his work was done as he leafed through papers high up on top of York Minster while he was on fire-watch duty during World War Two – making his efforts necessarily incomplete.

This was a very different experience of war for the author of the Steyning poem. He published a large quantity of historical research. Much of this is recorded by the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, of which he became President. He was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and of the Royal Historical Society. But John Stanley Purvis is best remembered for his invaluable translation of the York Mystery Plays, for which he won the OBE in 1958.

Canon Purvis was living with his sister Hilda when he died on 20th December 1968 aged 78. Hilda passed his vast collection of personal papers to those who had a special interest in his work. Her contact with Ernest Raymond identified the author of the Steyning poem for posterity. Ultimately, this contact also enabled Steyning Museum to gain the original hand-written version thanks to the kindness of Peter Raymond, Ernest’s son.

Further Information

Our article about Chanctonbury Ring is HERE.

There are 43 truly remarkable photographs taken by John Stanley Purvis during his World War I service, preserved in an album now held by the Green Howards Museum. See a BBC report HERE .

An account of the battle for High Wood is given at the World War One Battlefields website HERE. A discussion of battlefield tourism, prompted by the Purvis poem appears on the Heritage of the Great War website HERE. Actor Damian Lewis reads the poem High Wood on YouTube HERE.

Cranleigh School has produced a memorial website for both World Wars, including online copies of The Cranleighan school magazine which recorded many events HERE.

Graham Hine has recorded a YouTube video of his cycle ride along Mouse Lane HERE.

See our WWI article about The Day Sussex Died HERE.